Indian Heritage and Beauty within Coloured Identity

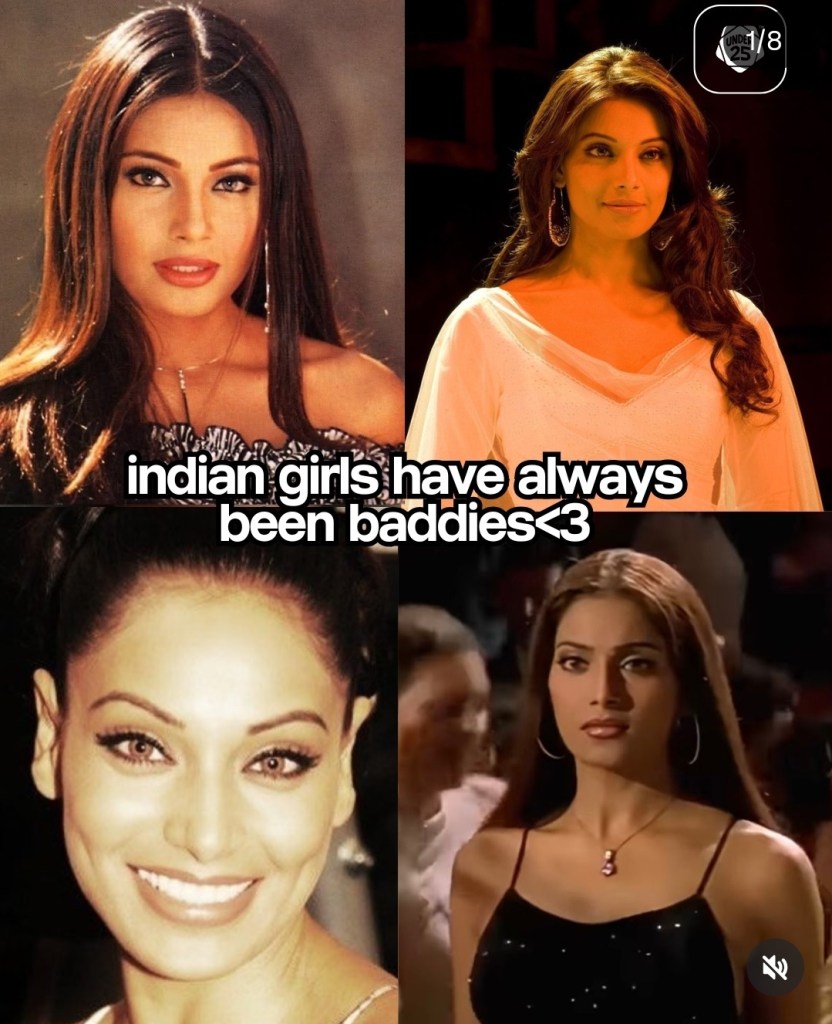

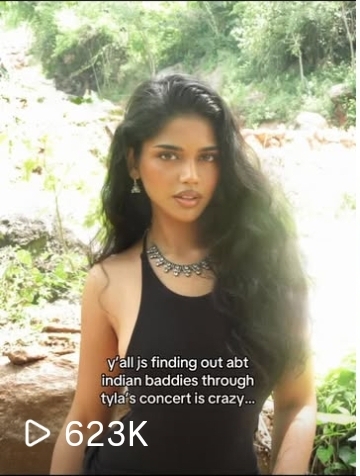

Tweets, Instagram posts and TikTok videos of young Indian women attending Tyla’s concert have gone viral, with bizarre captions stating that people “did not know” that “Indian baddies” exist. Juggernaut and other Indian/South Asian blogs have naturally responded to this pointing out what absurd commentary this is, considering that India has produced multiple Miss World and Miss Universe winners, as recent as 2021.

Historical explanations of the colonial ideas of ugliness have also been put up on social media, with people such as Snigdha Sur, the founder and CEO of Juggernaut, explaining how white beauty standards were used to justify colonialism and repression of Indian people’s human rights.

For me, as a Coloured woman, coming from the same ethnicity as Tyla, but from a different country, something else bothered me about this discourse. Coming from Zimbabwe, or Southern Africa generally, quite a different thing was said about beauty in relation to Indians. Both Zimbabwe and South Africa have experienced segregation, with South Africa experiencing the gruesome system of apartheid and Ian Smith’s government aspiring to follow it in what was formerly known as Rhodesia. Indian people would sit in front of Coloured and other mixed race people on buses and trains, for example, and Black people would sit right at the back. So this, in a way, communicated that Indian people occupied a higher place than Coloured and Black people, while still being beneath those who sat in front of them, such as the few Arab and East Asian people who were sometimes light enough to sit closer to white people if they were not, instead, grouped with Coloured or Asian people. Of course, white people sat right in front. This, therefore, communicated that Indian people were closer to a white beauty standard, therefore, far away from the ugliness associated with Black Africans.

Hair, for example, was a subject of ridicule for Black African women especially, with their hair texture becoming a source of mockery and exclusion. The pencil test, where a pencil was put through a person’s hair to identify their race, was used particularly when differentiating Coloured and Black people. The curlier or kinkier one’s hair, the more inferior they were considered.

Since Coloured people are of mixed ancestry, usually a continuous combination of African, Asian, and European ancestry, a certain ambiguity plays out in relation to their beauty standards. As they are still not white, they still exist as ugly and “repulsive” in the blue eye of the coloniser, but their mixedness gives them some “distance” from being fully Black.

For example, having somewhat lighter skin than many Black Africans brings them “closer” to a white beauty standard, as does their hair texture. While a person with kinkier hair may still be insulted with having “steel wool” or “kroes” hair, someone with a looser texture would be favoured as having acquired beauty.

So this is where my confusion to this reaction towards Indian baddies comes in. I grew up hearing that my own looks are attributed to Indian ancestry, totally erasing the contribution my African ancestors made to my face. Indeed, the particular Indian ancestry I have does give me lighter skin than others, but I could have been precisely the same shade I am if I only had African ancestry. So why is only one side of me afforded the gift of beauty? I have very little and very distant European ancestry, so I often do not get compared to White women, but I have seen Coloured people with more white ancestry having their looks attributed to that. However, for the purpose of this article, we will focus just on Indian and other Asian ancestry.

As is known, Asian ancestry that contributed to Coloured identity is usually traced back to Indonesia in terms of the earliest miscegenation amongst Africans and Asians in South Africa, and then with Madagascans, who equally have Afro-Asian ancestry, Later, Mauritians, Indians, and Sri Lankans come into the mix, as well as a few Chinese people. In the later part of the colonisation of Africa, more Indian people were brought in or encouraged to move, not only to colonial South Africa, but to early Rhodesia, therefore, increasing the very small Coloured population that had formed there. Segregation in Rhodesian schools, neighbourhoods and other places meant that Indian and Coloured people some times married each other due to proximity, thereby increasing the Asian heritage within the community.

Presentation of Coloured people varies widely due to this wide variety of heritage, and so, someone may present as “Asian-looking” while their own sibling looks “more white” or “more African” than them. If we compare just the ones that look “Asian” to the one who looks “African”, then the “Asian-looking” one is often considered more beautiful than the “African-looking” one, because they may have acquired curly rather than coily or kinky hair, or even wavy hair depending in their parents’ hair texture. They may have brown skin, but the type of brown, they “Indian look” to it, is favoured over the “African look.”

So for me, this is why this idea that there are “no Indian baddies” until Tyla comes around to expose them is a rather comical idea, having come from a place where Indians were said to be more beautiful than both Black and Coloured people.

For me, what this exposes is, of course, the heavy presence of colonial ideas, even in the so-called post-colonial, or rather, neo-colonial world. Non-white people are still regarded as ugly. And even when we consider the beauty of people of colour, it is often measured against the west. So for example, the idea of a “baddie” is associated with the United States of America.

It also exposes fetishes. As you have seen, Tyla herself has had her identity picked apart ridiculously, with Americans centring themselves and failing to understand identity formation and language use outside of their own settler colonial borders. But her sensuality is also a source of fetishism, which is no surprise considering the sexual stereotypes attached to mixed race women.

Indian women’s beauty is also being fetishized. We have known for decades that India has produced many global beauty pageant winners, but people have decided to be deliberately obtuse. Much of the response comes from the fact that these young Indian women are wearing “skimpy” outfits, defying the stereotype of Indian women in a saree, or having covered hair. India is associated with conservatism and moral policing of women’s dressing despite this actually being a global phenomenon and despite India itself having statues of goddess with bare chests.

Ironically, this is happening at a Tyla concert, and Tyla herself comes from another country associated with policing of women and having high rates of gender violence and femicide, where it is not exactly the safest to wear the outfits she does despite being a more liberal society in relation to its neighbours and other continental counterparts, such as Kenya and Zambia, for example, where cases of women being stripped naked publicly have taken place.

It also exposes general ignorance of the world outside us, something I find disturbing considering young people have their phone in their hand daily. Are we so stuck in our own algorithms and bubbles that we cannot do a simple Google Search about positive things in India, South Africa, or any other country? Young people should be some of the most culturally exposed and literate people considering their proficiency with this device.

To conclude, I will state the obvious, that we need to stop being ignorant. It is 2025. We should not be holding on to colonial ideas of beauty, and it should not be a surprise to anyone that beautiful women are found in every corner of the world, especially in a country that has over one billion people. Secondly, we should not be surprised to see women coming from large cosmopolitan cities such as Mumbai wearing western style “baddie” outfits, or even their own local traditionally-influenced style of “baddie” and revealing outfits, a phenomenon I hope begins to take wind and spread. Thirdly, women’s beauty, covered or uncovered, is not something to objectify and we should learn to appreciate it respectfully and without the desire for consumption.

The world of beauty, and the beauty within our world, are very vast and we should be educated and mature enough as a so-called modern society to view it outside of this limited imperial lens. We are a global society of eight billions, and should, by now, be appreciative of the eight billion types of beauty that present themselves on each of our faces.

Let us open our minds to new information with the goal to be educated rather than to have our eyes satisfied with capitalist ideas of attractiveness for conquest. We can coexist with beauty, and in fact, with ugliness, both of which are otherwise inconsequential things, but a vital part of our diverse world. The world is much too large and wonderful to concentrate on superficial things that, unfortunately, currently result in the material oppression and objectification of real people. Rather than opening up a world of possibilities for commodification, let us open up to the potential of a more peaceful and balanced cohabitation.

Sources:

Adhikari, M. (2009) Burdened by Race: Coloured Identities in Southern Africa

February, V. A. (2019) Mind Your Colour, London: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group

Le Roux, J. and Oyedemi, T.D. (2022) “Entrenched Coloniality? Colonial-Born Black Women, Hair and Identity in Post-Apartheid South Africa”, African studies, Volume 82, Issue 2, pp 200-214